Speaking to my friends that work for some of the big multinational banks, a comment that I have heard on more than one occasion is that they do not want to become the “dumb pipes” on which the financial system runs. For those of you outside of fintech and banking circles, the argument goes something like this: “Banks are getting bigger and increasingly more regulated, open banking is yet another regulation that forces us to give access to our customer data, enabling others to build products on top of our infrastructure while we become the pipes of the financial system, leaving banks to do the plumbing while fintechs steal our customers and capture all the riches and glory.”

While I cannot speak on behalf of big banks, looking back at history I am not sure that being the piping is such a bad thing. In fact, going back no further than the start of the last century, we can see that just like today’s headlines are dominated by the monopolistic power of big tech, the most pressing business issues in the early 1900s were around the dominance of the big “robber barons” that literally controlled the rails and piping of the emerging modern economy.

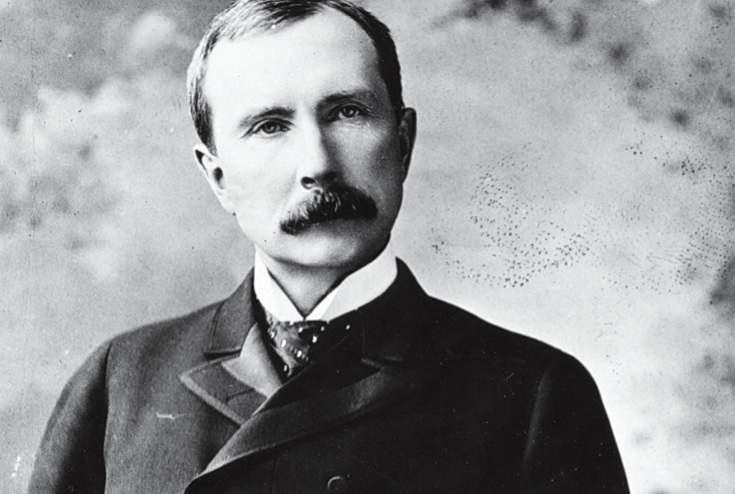

The first example that comes to mind is usually John D. Rockefeller, widely regarded as the wealthiest American of all time, (and possibly the richest person in human history) with his wealth worth nearly 2% of the US GDP at its peak. And while controlling 90% of the US oil and kerosene market in one of the most infamous monopolies of history was the key in paving his way to such riches, Rockefeller was equally focused on controlling the pipes through which this oil would flow. The first pipeline to carry oil was pioneered in 1863 by Samuel Van Sycle (the importance of this quickly became apparent to the Teamsters union who proceeded to try and destroy the pipeline which would take away their jobs) and it was not long after that in 1872 that Rockefeller had already bought United Pipe Lines, and by 1876 Rockefeller already controlled half of all the pipelines in the United States.

So Rockefeller certainly did not think of pipes as being “dumb” and neither did some of the other robber barons of the gilded age. In fact, when Rockefeller moved to New York in 1884, his 54th street residence was next to the mansion of William Henry Vanderbilt, whose father Cornelius had built up a vast family fortune with their railroad empire (not quite at 2% of GDP, but close).

There are clearly analogies here for our data driven economy almost two centuries later, and I am not just talking about the odd similarity between the oversized moustaches sported by the robber barons and Super Mario, the smart plumber of the digital age. The twenty-first century economy runs on data, and those who control the rails and pipes on which data flows can exert huge profits and influence. Whereas oil was referred to as the “black gold” of the gilded age, data is now the “cyber gold” of the information age. The importance of this is very clear in everything from Angela Merkel’s focus on how Europe is lagging behind the US and China on data platforms, to the fact that Mark Zuckerberg is making increasingly frequent trips to Capitol Hill. It is worth noting that over the last couple of centuries Zuck seems to have replaced the moustache with a hoodie, but the lack of gender diversity has not changed as dramatically as fashion has in the top billionaire ranks.

So how does this relate to the world of fintech and banking? For one thing, if I were a bank, I would be much more worried about not being the pipes versus vice versa. And rather than worrying about customers controlling (and being able to grant access to) their bank data with fintechs building new and innovative products using that access, I would worry about big tech companies such as Google or Tencent becoming the new pipes that power financial transactions.

The other lesson that banks today can glean from Rockefeller’s playbook was that in addition to his focus on using the pipes to gain a competitive advantage, one of his other business strategies was to standardise the kerosene and oil that he sold. (He did not name his company Standard Oil for nothing!) In fact, the combination of owning the pipes and gaining huge economies of scale resulted in the price of kerosene dropping by nearly 80% over the life of his company, while the standardisation resulted in improving the quality of the kerosene.

Standardisation has huge benefits, and just like the advent of containerisation dropped costs in logistics (moving the same amount of break-bulk freight in a container is about 20 times less expensive than conventional means), the advent of APIs today enables data to connect faster and orders of magnitude cheaper. In fact this sort of API-fication of data transmission is a leading driver of newly emerging fintech businesses such as Railsbank and Fidel API, both innovative companies founded in London with a global reach, and both very much happy to be the pipes that drive the innovation of other fintechs.

Bringing together banking and pipes in a final anecdote, I’d like to share a story that used to circulate in New York some years ago. In this story, a wealthy banker from Manhattan is organising a big party in his Hamptons weekend house, and hours before the guests are due to arrive, the plumbing in the house breaks down, flooding all the bathrooms. Desperate to get it fixed quickly, the banker calls a plumber who shows up immediately but gives him an astronomical quote to fix the pipes in short order. Shocked, the banker tells the plumber, “I am a banker and even I don’t make this kind of money!” To which the plumber replies, “I know, I used to work on Wall Street as well, but I decided to become a plumber.”