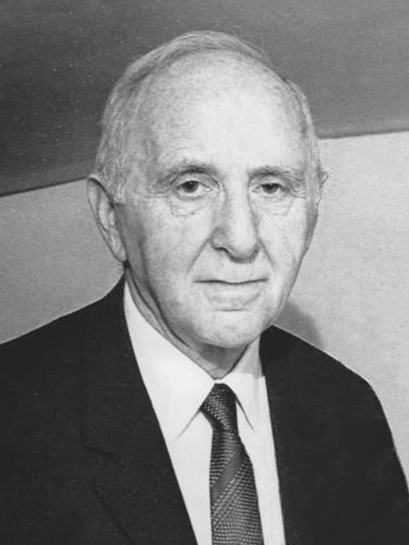

Remember Simon Kuznets. Mid-20th century economist, immigrant, and empiricist. He believed that economic output could be measured in a standardized form using mathematics and statistics and he gave the world the tool to do it: national income accounting and Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Born 1901 in what is today Ukraine, Kuznets emigrated to the United States in 1922 after the turmoil unleashed by the collapse of the Russian empire and the Bolshevik Revolution. He came of age during a time of depression and war and was fascinated by economic change and the big forces that shape it. In the 1930s-40s he pioneered systemic ways to measure economic production, income, and consumption across an entire economy, creating the concept of GDP and winning him the Nobel Prize in 1971.

A radical thinker, he was ever critical of the tool he had created, warning that it did not take into account inequality, unpaid work, and environmental damage, famously cautioning that “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred by a measure of national income.”

Despite cautionary warnings by its creator, GDP has nonetheless become the scoreboard of modern capitalism.

Until perhaps now. The advent of the AI economy and its profound implications may in fact be the death knell of this flawed but seemingly universal statistic.

Firstly, the core assumptions that back GDP are very specific and human labour centred: People work, firms hire, wages fund demand, output is scarce, production is costly, and prices signal value. Human capital, and the productivity of it, is one of the binding constraints on growth.

In a modern AI economy the constraint on growth shifts away from labour to compute, energy, data, capital, and raw materials. In this new world, rare earths and energy matter more than office workers. As a result, economic returns will increasingly shift to owners of capital and natural energy resources away from labour. This has the risk of creating huge income inequalities as the old economic models that tie wage growth to economic growth start breaking down.

In this new paradigm, output no longer equals employment, productivity no longer equals income, and growth no longer equals welfare.

Secondly, demand side metrics such as GDP will start becoming more misleading. One example of a potential paradox is that AI agents may produce lots of output, very cheaply, on the surface looking like GDP is actually contracting (as it measures prices).

This will likely bring with it a shift to more supply focused measurements that take into account how much natural resources an economy has access to. As the framework shifts towards the quantity of energy and raw materials we can harvest, issues around environmental balance will become unavoidable.

On the one hand we will have a hungry machine that demand energy and natural resources at enormous scales, while on the other hand we will have the spectre of global warming and environmental imbalance. We will need to make choices between harvesting the “free” resources of the environment versus more economic growth, and the current framework of GDP is not equipped to properly account for debit and credit side of this trade off.

It is very likely that a new sort of politics that address wealth re-distribution and environmental factors will start to emerge across the world, and we are in fact seeing early examples of this today in many places. Likewise, a new geopolitics focused on energy, data, compute, and natural resources is already emerging.

What is ultimately at stake is not a better statistic, but a better understanding of power. GDP told us who was productive in a labour economy. AI demands that we understand who controls energy, compute, data, and capital in a post-labour one. Measurement shapes policy, and policy shapes outcomes. When the measure fails, politics fills the gap.

GDP was the right tool for an industrial century. The AI age will require something harder, more physical, and more honest, one that acknowledges that growth is no longer constrained by human effort alone, but by energy, resources, and the choices we make about how to deploy them.